The Myth of Safety: Why Cash Is Not Neutral After 40

How inflation, time and longevity quietly reshape risk for women in the second half of their financial lives

📕Special note: The Billion Dollar Blindspot (the book) is almost ready to step into the world. If you want to follow the journey, early excerpts, behind-the-scenes notes, and launch news, you can sign up for early access here.

Here are 5 ways to support my work: 1. click “❤️” to amplify 2. subscribe 3. share this publication 4. buy me coffee 5. become a partner.

In the early 2000s, banks began marketing a new idea as a form of prudence: “sweep accounts.” The idea was simple. Idle cash would be automatically moved out of checking and into savings to earn an interest while remaining instantly accessible. It was presented as a small upgrade; a smarter way to hold money without taking risk.

After the 2008 financial crisis, that instinct hardened into doctrine. Millions of Americans pulled money out of the financial markets and parked it in savings accounts. The intention was to wait until things felt stable again. Cash became synonymous with responsibility. Volatility meant danger. Liquidity meant control.

For years after the crises, interest rates collapsed and remained near zero for almost a decade. Inflation, while muted at first, was continued compounded quietly in the background. By the time it surged in 2021–2022, a decade of purchasing power had already been lost.

That caution had a cost most didn’t see until much later.

This is Part 2 in a twelve-part series for women over 40 who want to understand how money really behaves so the next decade works for them and not against them.

Most of us learned that responsible money management meant holding cash in a savings account. That instinct isn’t irrational. Having liquidity feels prudent. After volatility, life transitions, or uncertainty, cash in a high-yielding savings account feels like the one decision that can’t go wrong.

The problem is that the system around it has changed.

What the Numbers Actually Say About High-Yield Savings Accounts

On the surface, high-yield savings accounts (HYSA) still appear attractive. Some U.S. providers advertise rates near 4.30% APY, with competitive accounts clustered around 3.90–4.25%. Compared to the national average savings rate (still under 1%) this looks compelling.

But those headline numbers mask four structural realities.

First, interest rates are variable

The Federal Reserve began cutting rates in 2025. The federal funds rate now sits around 3.50–3.75%, with markets pricing in further easing through 2026. High-yield savings accounts are variable by design. When rates fall, yields on those savings accounts adjust downward often without notification, and always without your consent. A 4.5% account today becomes 3.5%, then 3.0%. The balance itself never signals that anything has changed.

Second, inflation doesn’t stop working.

U.S. inflation (as measured by the CPI) stood around 2.7% year-over-year in late 2025, with core inflation close behind. Even though nominal savings yields exceed inflation, the margin is thin and easily erased once taxes enter the picture.

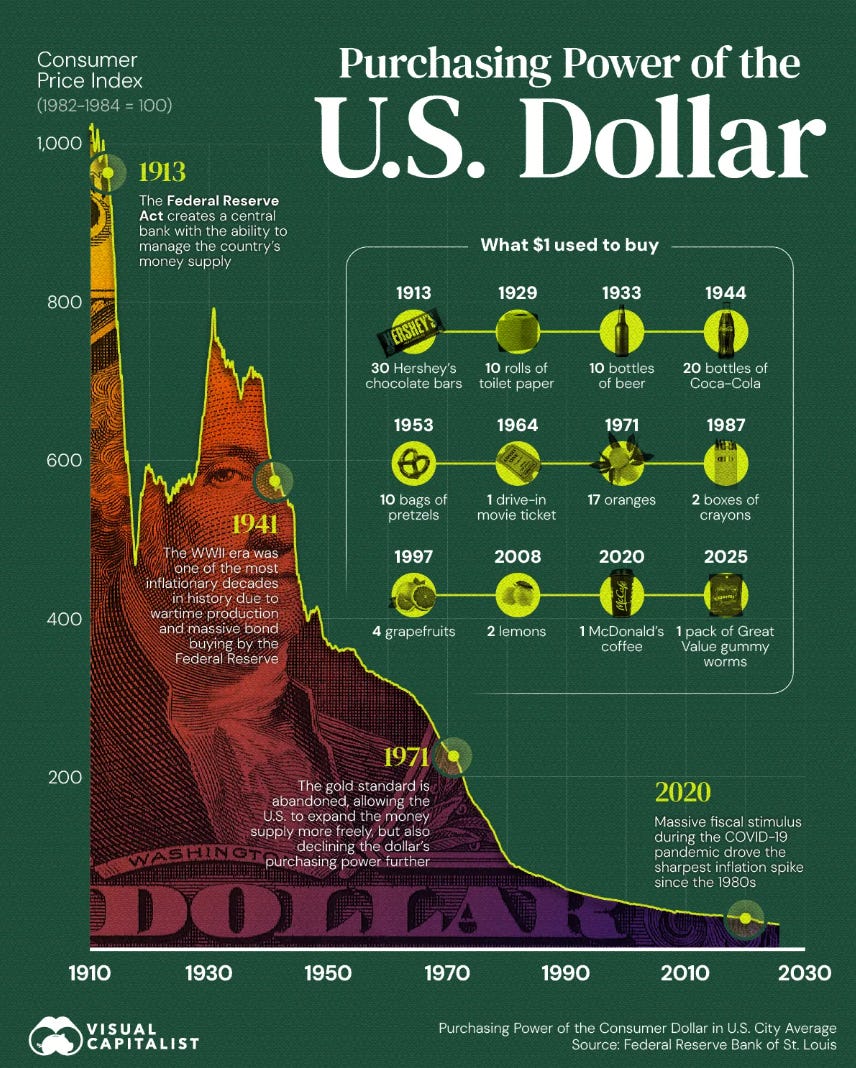

Consider what this means over time. In 1971, when the dollar was no longer backed by gold, $100 could buy what requires approximately $750 today, based on U.S. CPI data. That is the compounding effect of monetary expansion over five decades.

So if we project forward (conservatively assuming 2.5–3.0% average inflation) $100,000 held in cash today will have the purchasing power of roughly $55,000 in 20 years, and $40,000 in 30 years. The nominal number ($100,000) stays the same but what it can buy in the real economy does not.

Third, taxes matter more than most realize.

Interest earned in savings accounts is taxed as ordinary income. If you are in your peak earning years (which many women in their 40s and 50s are), you are likely facing marginal tax rates of 22–37%. After federal and, in many cases, state taxes, the real after-tax return on cash often lands near zero. Sometimes its negative!

Fourth, there’s the opportunity cost of time.

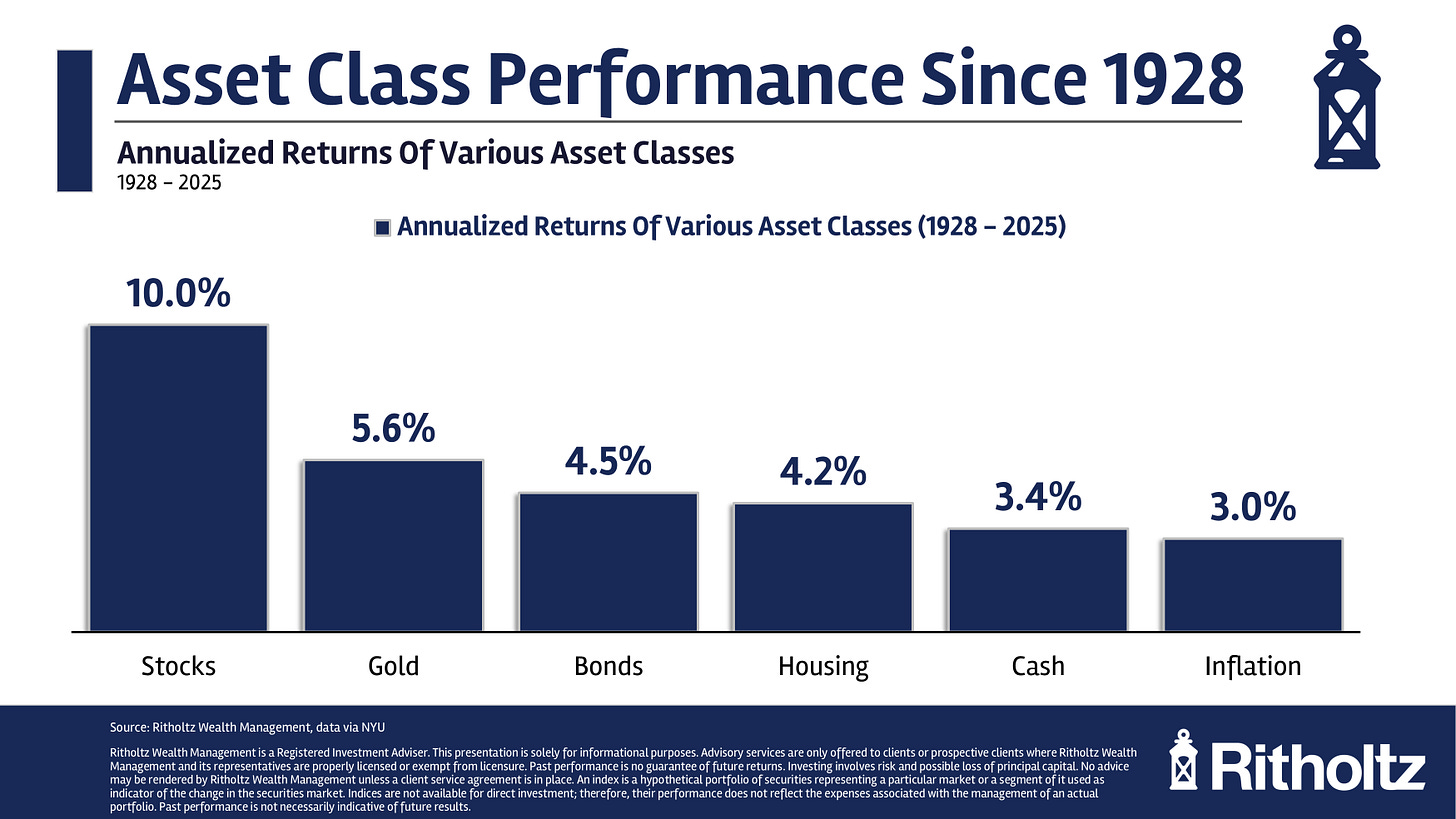

Cash offers safety and liquidity. It does not compound. Historically, diversified equities have delivered long-term returns well above inflation. Money that isn’t needed within the next 3–12 months and remains in cash for years quietly forfeits compounding.

How Financial Risk Changes for Women After 40

The shape of financial risk changes in this life stage because of structural asymmetries most financial planning doesn’t account for.

Longevity risk:

Women live longer than men often by five to seven years. That’s an additional decade of expenses, medical costs, and inflation exposure. A portfolio designed for a 20-year horizon is fundamentally mis-sized for a 35-year reality.

Timing risk:

Many women experience career interruptions for children, elder care, or supporting a partner’s relocation. Earnings paused or compressed during years when compounding matters most reduces margin for error later.

Liquidity risk:

Women are more likely to become primary caregivers again this time for aging parents or unwell partners. These costs are often unplanned and arrive precisely when financial flexibility is expected to increase.

Delegation risk:

For many women, financial decision-making was deferred earlier in life as part of divided labor in a partnership. Divorce, widowhood, or a need to take control often arrives alongside a portfolio they did not design and do not fully understand.

These aren’t edge cases. These are structural realities affecting the majority of women in this demographic. Yet much of the financial industry continues to manage women’s capital as though it belongs to a 55-year-old man with a linear career, uninterrupted earnings, and a single pension pool.

Why This Stage Is About Optimization

Some women arrive here after a sudden capital event; divorce, inheritance, or a business sale. Others arrive after decades of steady saving. Either way, this phase is no longer about accumulation at all costs. That window has largely passed.

But it is not yet about traditional capital preservation either. Most women in this stage still have decades of economic life ahead. This is the optimization and positioning phase. The question is no longer “How do I grow wealth at all costs?” It’s “How do I structure what I have so I don’t outlive my money?”

In Week 1, I introduced the idea that capital plays different roles; stability, growth, and durability and strategic 👇.

So the real question at this stage of life is not how to avoid risk altogether, but how to ensure that the growth and durability pillars of your capital are doing enough work so that your longevity does not become a silent liability.

Why Women’s Health Is a Long-Duration Capital Opportunity

Women’s health investing tends to sit within the growth and durability pillars of capital because it is long-term and exhibits timing asymmetry.

The women’s health market is already a large, multi-tens-of-billions-dollar market when it is narrowly defined (femtech, diagnostics, digital health).

However, when you broaden the lens to include pharma, medical devices, fertility, menopause, cardiometabolic health, maternal health, oncology, autoimmune disease, and chronic care, the addressable market in women’s health runs into the hundreds of billions.

The demand for women’s health solutions is real due to biology gaps in existing healthcare solutions, demographics are undeniable (aging female population, longevity) and Institutional capital is still early relative to the size of the opportunity. Taken together, this confluence of factors is creating a favourable tailwind for women’s health investors.

Opportunities to invest in women’s health exist both in:

the public markets through stocks (equities) and funds

and in the private markets, where you can make direct investments into companies or private funds solving specific women’s health problems.

Most of the opportunities are in the private markets but there is an access asymmetry in private markets. Not everyone sees the same dealflow. Not everyone gets the same terms. And not everyone understands how access actually works.

In Week 3, I'll walk through why the private markets look and feel opaque and why that opacity isn't a bug but a feature. We'll examine how access actually works and how you can recognize when access is a matter of structure rather than exclusion.

Paid members join my Monthly Investment Committee, where we walk through real (anonymized) women’s health investment pitches together step by step. You learn how experienced investors think about:

what matters

what doesn’t

and where first-time investors usually misread risk

Over time, you stop guessing and start recognizing signal.

→ Join the Monthly Investment Committee | $29/month

If you want the broader lens behind this framework, my upcoming book The Billion Dollar Blindspot explores how capital actually flows and why women’s health remains one of the most mispriced areas of healthcare investing.

Join Our Network

If you are building or backing credible, under-the-radar solutions in women’s health, we curate and occasionally review select opportunities with our investor community as part of our learning process. If your work would contribute meaningfully to that discussion, reach out privately.

I write weekly at The Billion Dollar Blindspot about capital, care, and the future of overlooked markets. If you are building, backing, or allocating in this space, I’d love to connect.

Disclaimer & Disclosure

This content is for informational and educational purposes only. It does not constitute financial, investment, legal, or medical advice, or an offer to buy or sell any securities. Opinions expressed are those of the author and may not reflect the views of affiliated organisations. Readers should seek professional advice tailored to their individual circumstances before making investment decisions. Investing involves risk, including potential loss of principal. Past performance does not guarantee future results.